Almost Family · La vita alla palazzina numero undici

“The reason I came to Shanghai was to not eat instant noodles. Now, I’m running out of even those.”

🇮🇹 Scorri più in basso per leggere in italiano · Scroll further down to read it in Italian.

Shanghai, April 2022

“Second floor! Come down and do your test!”

“What did you say?”

“Come down and do your test! You’re the only ones missing!”

“Okay! I’m in the shower!”

“Come on!”

“Alright! Give me a minute!”

During my first six months in this old Shanghai alleyway, there had always been a distance between me and the senior couple living downstairs. The only time we interacted was on a late October weekend. I wanted to go out, but couldn’t find my apartment keys.

In my mind, I quickly went over my possessions: nothing worth a lot of money. I used an unopened package from something I had bought online to keep the door from closing, and left the apartment.

But the building door downstairs was still a problem — between the time I left and when I came back, someone would have shut it. Waking up Mr. and Ms. Yu by knocking late at night wouldn’t have been very neighborly. I decided to spend the night outside and go home in the morning.

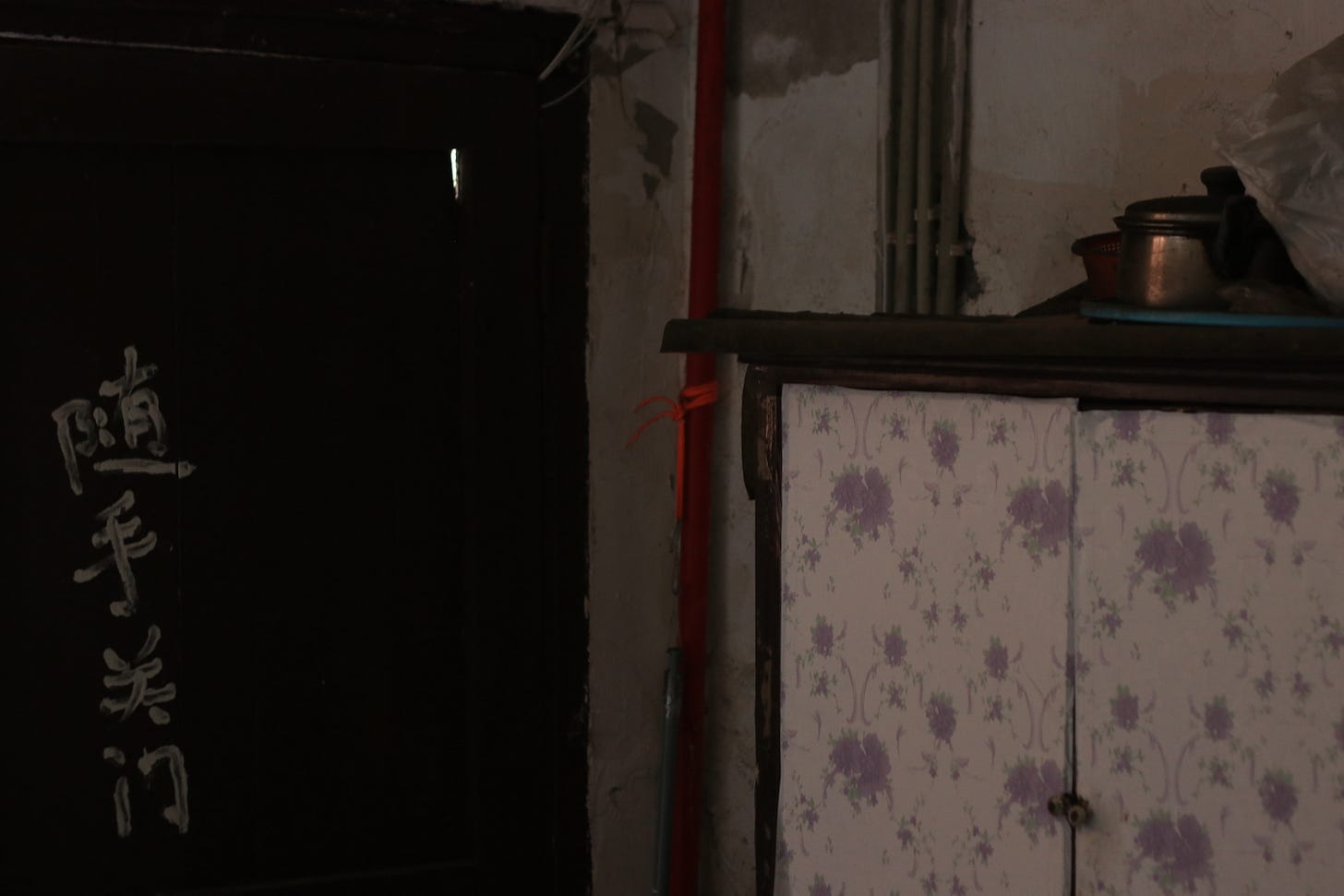

Old Shanghai houses have shared kitchens in the staircase. As I arrived outside of the building, I could see through the window Mr. Yu boiling four eggs. He recognized me and opened the door; I explained who I was and what had happened. “You forgot the keys,” Mr. Yu said smiling, repeating my words to make conversation. I smiled back.

After that day, it was only polite nods and good mornings on my way out. That’s until Shanghai went into lockdown.

Building 11 is a three-story Shanghai alleyway house. The Yu’s occupy the ground floor; two young men and I live on the first floor; a family of four is on the third. Every time we go for a Covid test — a daily recurrence in lockdown life — we wait for all nine of us to be fully gathered downstairs before heading to the sampling site. We look like a tight pack of primary school students.

The notice we had received in Puxi, the part of Shanghai to the west of the Huangpu River, said that lockdown would last from April 1 to April 4. But on April 5, it just went on.

That day, as I left my apartment to go for yet another Covid test, I met Mr. Yu. “Today’s the last one,” he said with a cheerful smile. “If all goes well, tomorrow we’re free.”

I didn’t think that was true. The lockdown had just been extended, indefinitely. Mr. Yu couldn’t know when it was going to end — no one did. But I found solace in his lighthearted optimism, and tried hard to be persuaded by it.

Mr. Yu was born in the ’30s. Before the founding of Mao’s China in 1949, he went to a middle school run by the French in Shanghai. He learned English, French, and Russian, and once expressed regret for not being able to converse with me in Italian, my mother language. Our residential complex was designed and built in 1929: Mr. Yu was born here, and called it home ever since.

Before the Communist Party took over and split Shanghai’s single alleyway houses into multiple living units, all of Building 11 belonged to Mr. Yu’s family. In his over ninety years, Mr. Yu saw all that there was to be seen in history — and even what one might wish not to. Could the spread of a virus really disrupt his inner peace? The more I think about it, the more I understand his unperturbed look.

With the onset of lockdown, their family routine didn’t change. Mr. Yu chops vegetables at home; Ms. Yu chats the day away with neighbors sitting outside. That’s the background noise to my lockdown days, spent working from my terrace that overlooks the alleyway. They use part Shanghainese dialect and part Mandarin, so I can get about half of what they say.

We have plenty of neighborhood group chats on our phones, but key information still reaches us through Ms. Yu. To know when we have to go downstairs to pick up government vegetables or antigen test kits, we came to rely on Ms. Yu’s lively voice calling us, or sometimes on her fierce knocking on the door.

Next to my apartment is a small back room called the “pavilion room,” or tingzijian. Before lockdown, it used to house three young men. They would sleep at day and work at night, joining the troupe of helmet-wearing, for-hire designated drivers who ride in folding bicycles to barbecue restaurants and karaoke bars. In the line for our Covid test, we talked, and I found out that one of them had recently gone back to his hometown. As luck would have it, Omicron reached Shanghai in the meanwhile, and he remained stuck outside.

That made the tiny tingzijian slightly larger for the two guests left. Ms. Yu amiably addresses them as “the two kids”.

In the first ten days of lockdown, as a limited amount of drivers struggled to serve a city of 26 million, getting groceries delivered was a challenge. Most people were down to eating whatever was left at home. Scrolling through my WeChat, I saw a post by Li Ming (a pseudonym), one of the young men in the tingzijian. “The reason I came to Shanghai,” his words read, “was to not eat instant noodles. Now, I’m running out of even those.” Shanghai felt like a faded dream.

The tingzijian is not meant for cooking — normally, the “kids” would just get delivery food or eat outside. Ms. Yu inquired more than once about their food situation. She said they could give her the vegetables provided by the government, and she would do the cooking. From what I saw, they never took up the offer. They would just rinse the vegetables and eat them raw.

Eventually, Ms. Yu got them a rice cooker. That night, looking a bit tipsy, Li Ming knocked on my door asking for some cooking oil. The next time he came, he was holding a five-pound bag of rice. As he gave it to me, he only said two words: “Government gift.”

The morning when Ms. Yu called me out of the shower, I was barely halfway done. I put something on quickly and ran downstairs. There was no one in line at the sampling site, and paramedics were packing things up. I was clearly late to the party.

Back at Building 11, I ran into Mr. Yu, who was cooking lunch. “Today we went to see the doctor,” he said, and I stopped, realizing he had something to say to me. “That’s why we didn’t call you for the test.”

Although the sound of loudspeakers fills the alleyways for most of the day, there are just too many buildings mentioned in the announcements, which makes it easy to miss the one you should hear. That’s why, at Building 11, we only respond to Ms. Yu’s calls, and ignore the rest. When testing had started earlier that morning, Mr. and Ms. Yu were at a doctor’s appointment. That’s why I had almost missed it.

“I had to get a pass from the residential committee to be able to go out,” Mr. Yu said, as if the red tape required, and not the doctor’s appointment itself, was what occupied his thoughts. In the past few days, I noticed how Mr. Yu has carried a much weaker look.

“How are you,” I say to Mr. Yu with a pause, almost trying to buy time, avoid finishing my question and delay the moment I will hear the answer. “How are you feeling?”

“So so,” says Mr. Yu. This time, his cheerful tone creates a stark contrast with the meaning of his words.

I now realize what has happened in about three weeks of lockdown: shouting back to Ms. Yu from the shower, checking on Mr. Yu’s health after his doctor’s appointment. The distance between us is gone. For the first time, I talked to them directly, without making the conscious effort to come off as the polite upstairs neighbor. That feeling you usually get at home, of talking with mom or dad and not thinking too much about it — because you know there will be countless other chances for conversation about anything, for all sorts of reasons in the near future. Every exchange grows to be ordinary, a product of inertia, a part of your day. It becomes life.

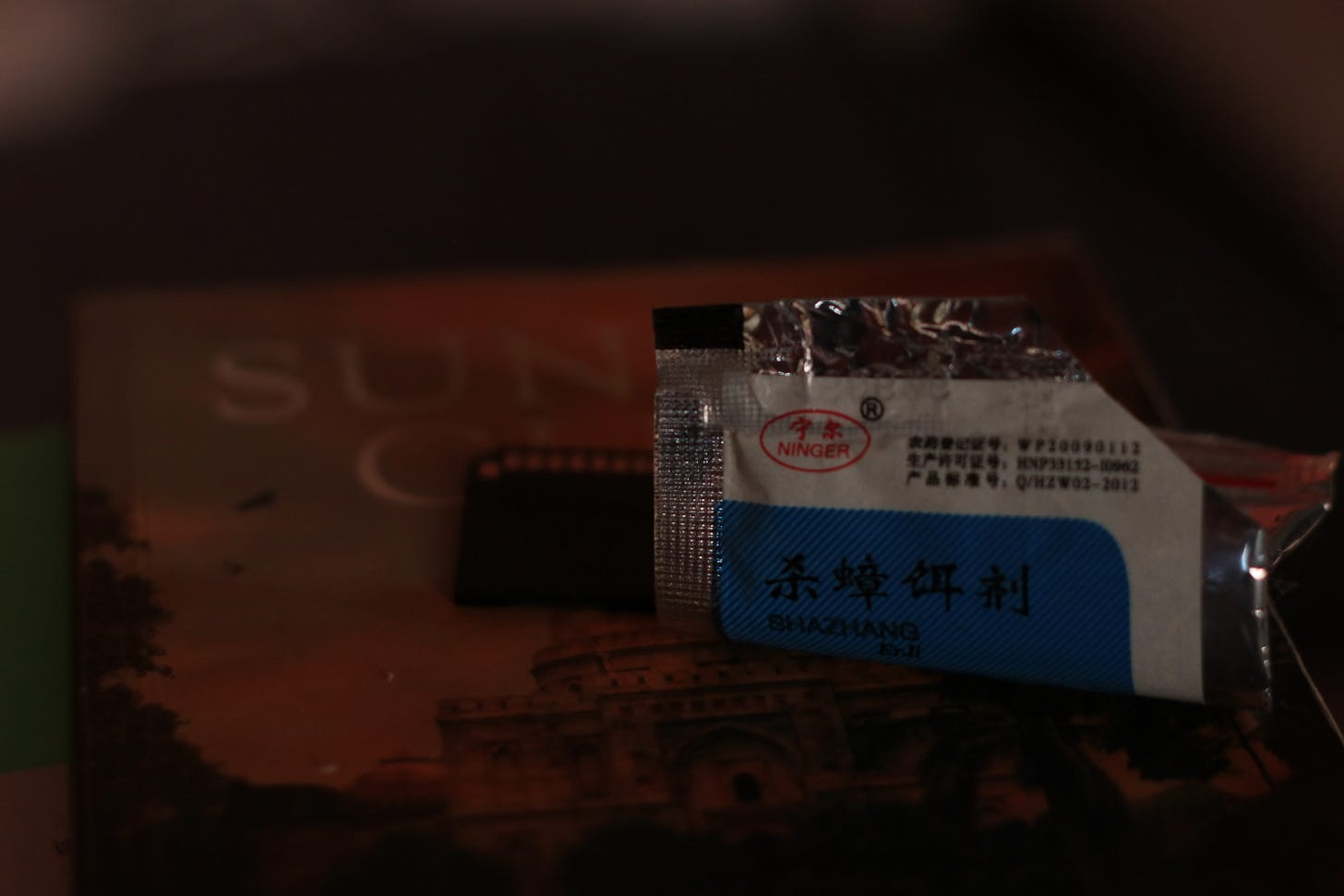

“Did it get them?” Ms. Yu asks me excitedly. The other day, she gave me a small packet of roach powder, although we had never discussed this topic before, nor had I ever suggested I had a roach problem.

“Oh,” I say, unable to immediately understand what Ms. Yu is talking about. “It did, yeah!”

“You see, this powder works great,” Ms. Yu says proudly. “You just put a little bit down, and you can use it for years.”

“You’re right,” I say as I walk up the stairs. “Works like a charm!”

Back in my apartment, my gaze falls on the cupboard, on which lies the unopened packet of roach powder.

This article was originally published by the Sixth Tone. It competed in its 2022 China Writing Contest, and won first prize in the short form nonfiction category. Below is an Italian version of the article. A Chinese version is available here.

Italian Version ☕️ 🇮🇹

La vita alla palazzina numero undici

Shanghai, Aprile 2022

“Secondo piano! Scendete a fare il tampone!”

“Che cosa?”

“Scendete a fare il tampone! Mancate solo voi!”

“Va bene! Sono in doccia!”

“Veloci!”

“Va bene! Arrivo!”

Nei miei primi sei mesi in questo vecchio quartiere shanghainese, c’era sempre stata una certa distanza nei rapporti con l’anziana coppia al piano di sotto. L’unica volta che avevamo avuto un vero e proprio scambio era stato in un weekend di fine ottobre. Stavo uscendo di casa e non trovavo le chiavi.

Ho pensato velocemente a quello che avevo in casa: nulla di grande valore. Ho usato una scatola di cartone con dentro qualcosa che avevo comprato su Taobao per tenere la porta aperta, e sono uscito.

Ma il portone della palazzina al piano di sotto rimaneva un problema, perché qualcuno l’avrebbe chiuso mentre ero via. Svegliare la famiglia Yu bussando a notte fonda non mi avrebbe fatto vincere il premio per vicino dell’anno. Decido di passare la notte in giro e di tornare il mattino.

Le vecchie case di Shanghai hanno storicamente una cucina condivisa nel vano scala. Arrivato al portone della palazzina, intravedo dalla finestra il Signor Yu che sta bollendo quattro uova per la colazione. Lui mi riconosce e viene ad aprire. Spiego chi sono e cos’è successo, ma lui è veloce a capire, e mi ripete in inglese l’imprevisto che gli ho appena illustrato in cinese: “You forgot the keys.” Sorrido e lo ringrazio.

Dopo quella domenica, ci sono stati solo cenni con la testa e dei buongiorno di fretta mentre uscivo di casa. Fino a che Shanghai è andata sotto lockdown.

La palazzina numero undici è una vecchia casa shanghainese di tre piani. Gli Yu abitano al piano terra; io e altri due ragazzi siamo al primo piano; e una famiglia di quattro persone vive al terzo. Ogni volta che andiamo a fare il tampone (una ricorrenza quotidiana in tempi di lockdown) aspettiamo fuori dal portone al piano di sotto che tutti e nove i residenti della palazzina siano scesi. Poi procediamo insieme verso il tendone dei paramedici. Sembriamo una scolaresca.

L’avviso che avevamo ricevuto a Puxi, la parte di Shanghai a ovest del Fiume Huangpu, diceva che il lockdown sarebbe durato dall’1 al 4 aprile. Ma arrivati al 5 aprile, il lockdown è andato avanti.

Quel giorno, quando sono sceso a fare il tampone, ho incontrato il Signor Yu. “Oggi è l’ultimo,” ha detto con un sorriso felice. “Se tutto va bene, domani siamo liberi.”

Non mi sembrava credibile. Il lockdown era appena stato prolungato, fino a data da destinarsi. Il Signor Yu non poteva sapere quando sarebbe finito: nessuno lo sapeva. Ma trovavo conforto nel suo spensierato ottimismo, e cercavo di farmi convincere.

Il Signor Yu è nato negli Anni Trenta. Prima della nascita della Cina di Mao nel 1949, il Signor Yu è andato a una scuola media gestita dai francesi a Shanghai. Ha imparato inglese, francese e russo (e si è una volta detto dispiaciuto di non poter conversare con me in italiano). Il nostro quartiere è stato progettato e costruito nel 1929: il Signor Yu qui ci è nato, e ci è rimasto per sempre.

Prima che il Partito Comunista prendesse il potere e dividesse le vecchie case monofamiliari di Shanghai in più unità abitative, tutta la palazzina numero undici apparteneva alla famiglia del Signor Yu. In oltre novant’anni di Storia, il Signor Yu ha visto tutto quello che c’era da vedere, e anche quello che uno preferirebbe evitare. Era possibile che la diffusione di un virus potesse sconvolgere la sua pace interiore? Più ci pensavo, e più comprendevo la calma olimpica scritta sul suo volto.

Con l’inizio del lockdown, le loro abitudini familiari non sono cambiate. Il Signor Yu taglia le verdure a casa; la Signora Yu passa le giornate seduta fuori a chiacchierare con le vicine. È questo il rumore di sottofondo del mio lockdown, passato a lavorare da un terrazzo che si affaccia sulla stradina del quartiere. Le signore parlano un po’ in dialetto shanghainese e un po’ in mandarino, quindi capisco circa metà di quello che dicono.

Siamo pieni di gruppi WeChat per i residenti del quartiere, ma le comunicazioni importanti ci arrivano comunque per voce della Signora Yu. Per sapere quando c’è da scendere a ritirare le verdure del governo o i test rapidi, abbiamo imparato ad affidarci ai suoi energici schiamazzi. Se lo ritiene necessario, la Signora Yu sale direttamente le scale e bussa alla porta vigorosamente.

Affianco al mio appartamento, c’è uno stanzino di pochi metri quadri. Prima del lockdown, ci vivevano tre ragazzi. Dormivano di giorno e lavoravano di notte, unendosi alle truppe di autisti a chiamata che girano con casco e biciclette pieghevoli per andare a prendere clienti alticci fuori da ristoranti e bar karaoke. Parlando mentre eravamo in coda per il tampone, ho scoperto che uno di loro tre era da poco tornato nella sua città natale. Nel frattempo era arrivato Omicron, e lui era rimasto chiuso fuori da Shanghai.

Così, lo stanzino era diventato un po’ più grande per gli inquilini rimasti, che la Signora Yu chiama amabilmente “i due bambini”.

Nei primi dieci giorni di lockdown, i pochi fattorini in giro per la città facevano del loro meglio per riempire le dispense di ventisei milioni di abitanti: farsi consegnare la spesa era diventata un’impresa ardua. I pasti erano regolarmente a base di “quello che è rimasto”. Guardando fra i post dei miei amici su WeChat, ne avevo visto uno scritto da Li Ming, uno dei due inquilini dello stanzino. “Il motivo per cui ero venuto a Shanghai,” scriveva, “era non dover mangiare più instant noodles. Ora, ho quasi finito pure quelli.” Shanghai era come un sogno sfumato.

Quello stanzino non è pensato per cucinare. In tempi normali, i “bambini” ordinavano a domicilio o andavano a mangiare fuori. Durante il lockdown, la Signora Yu si è informata più volte sulla loro alimentazione. Ha detto che avrebbe potuto cucinare per loro le verdure del governo. Ma da quello che ho visto, non hanno mai accettato la sua offerta. Si sono limitati a mangiare le verdure crude dopo averle passate velocemente sotto l’acqua.

A un certo punto, la Signora Yu si è procurata per loro un cuociriso elettrico. Quella sera, con un aspetto un po’ brillo, Li Ming mi ha bussato alla porta per chiedermi dell’olio da cucina. La volta dopo si è presentato con in mano un pacco di riso da cinque chili. Me l'ha passato dicendo solo tre parole: “Regalo del governo.”

Ero nel mezzo di una doccia la mattina in cui la Signora Yu mi ha chiamato a squarciagola dal pianoterra. Mi son vestito in fretta e sono sceso. Non c’era coda per fare il tampone, e i paramedici stavano per andarsene. Chiaramente ero l’ultimo arrivato alla festa.

Tornato alla palazzina numero undici, incrocio il Signor Yu, che sta preparando il pranzo. “Stamattina siamo andati dal dottore,” mi dice, e mi fermo capendo che ha qualcosa da dirmi. “Per questo non vi abbiamo chiamati per il tampone.”

Anche se il suono dei megafoni riempie le stradine di quartiere per quasi tutto il giorno, gli annunci parlano di troppe palazzine, ed è facile perdersi proprio l’annuncio che dovresti sentire. Quindi, alla palazzina numero undici, rispondiamo solo alle convocazioni della Signora Yu e ignoriamo il resto. Ma quella mattina, quando erano iniziati i tamponi la famiglia Yu era all’appuntamento col dottore e io ero rimasto ignaro di tutto.

“Ho dovuto farmi dare una certificazione dal comitato residenziale per poter uscire,” dice il Signor Yu, come se a occupare i suoi pensieri non fosse l’appuntamento dal dottore in sé, ma la burocrazia richiesta per arrivarci. Negli ultimi giorni, ho notato che il Signor Yu ha un aspetto più debole.

“Tutto bene?” Chiedo al Signor Yu, con una pausa che divide la domanda in due parti, come a guadagnare del tempo prima di dover sentire la risposta. “Di salute, dico.”

“Così così,” dice il Signor Yu. Questa volta, il suo tono allegro è in netto contrasto con il significato delle sue parole.

Ora capisco cos’è successo nelle ultime tre settimane: rispondere urlando dalla doccia alla Signora Yu, informarmi sulla salute del Signor Yu dopo il suo appuntamento. Non c’è più distanza. Per la prima volta, ho parlato loro in modo diretto, senza lo sforzo consapevole di voler apparire come il vicino educato del piano di sopra. Quella sensazione che hai a casa, di parlare con i tuoi genitori e di non darci peso, perché sai che ci saranno altri mille motivi di conversazione nei giorni e nei mesi a venire. Ogni dialogo diventa quotidianità, prodotto dell’inerzia, parte della giornata. Diventa vita.

“Li ha presi?” La Signora Yu mi chiede entusiasta. Qualche giorno fa, mi ha dato una bustina di polvere per scarafaggi, anche se non avevamo mai toccato questo argomento in passato, né avevo mai suggerito di avere un problema di scarafaggi a casa.

“Ah,” dico, non capendo, in prima battuta, di che cosa stesse parlando. “Li ha presi, sì!”

“Vedi, questa polvere funziona benissimo,” la Signora Yu dice inorgoglita. “Basta metterne pochissima. Ti dura per anni.”

“È vero,” dico salendo le scale. “Funziona alla grande!”

Varcata la porta di casa, il mio sguardo cade sulla bustina di polvere per scarafaggi: è ferma sul mobile da tre giorni, ancora sigillata.